Photo Credit: A.D.A.M Inc.

Arthur: Janet N. Zadina, Ph.D. Cognitive Neuroscientist, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA. www.brainresearch.us.

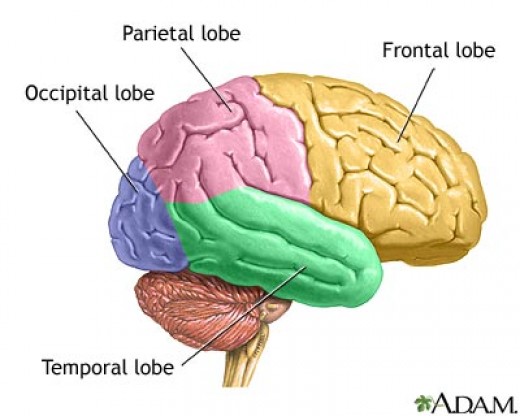

In a study lasting many years, first grade teachers observed a behavior that predicted school and life outcomes. This important behavior is known as executive function, governed by the frontal lobes of the brain. Executive function is observed in early childhood as the ability to control one’s behavior. Researcher Terrie Moffitt reports that, based on teacher observation, the child’s ability to stand in line, raise a hand before speaking, or keep quiet when asked predicted academic achievement, income, criminality, and drug use at age 32.

It is crucial that we develop good executive function in our children as early as possible. In fact, according to neuroscientist Philip Zelazo, frontal lobe executive function in childhood is a better predictor of school readiness than IQ. Let’s look at the brain to get a broad understanding and then examine what parents and teachers can do.

The frontal lobe is one of the four lobes (major sections) of the brain and is located behind the forehead. The frontal lobe can be thought of as the “conductor” of the brain’s orchestration. It is associated with the term executive function because it acts as an “executive” – planning, organizing, budgeting time and resources, and making good decisions. In healthy brains, it also regulates emotion and attention. For example, people with poor frontal lobe function might fly into a rage when they get angry, whereas healthy individuals would process the emotion in the frontal lobes and choose appropriate reactions.

Executive function begins developing in early childhood and continues developing until around ages 18- 25. Of course, we can always improve our frontal lobe functions throughout life, but this is the time of greatest change and development and the ages during which interventions could be most helpful.

Because the quality of executive functioning in a child can predict success or failure in life and school, it is critical that we take steps to develop these functions. How do you develop a skill in the brain? Like any part of the brain, it develops through use. By having children use executive function skills, they will develop them. It is helpful to think of the brain like muscles – the more you use each one, the better it gets. Therefore, we start early and continue throughout education to teach and require executive functions skills. The list of executive functions is long, but a few are especially relevant to early childhood.

• Controlling impulses and attention

• Regulating emotion

• Planning

• Judgment

• Problem-solving

• Metacognition (thinking about one’s thinking, reflection, insight)

Work with your child daily to develop these skills. Ask them to wait quietly in the grocery line, for example. Start with small increments of time and work up. Praise them for controlling their behavior. Even asking a child to say “please” and “thank you” helps them to develop the ability to think about their behavior and control it. Give them games that require sustained attention, rather than allowing them to watch too much television, which contributes to shorter attention spans. Require children to stop, look, and listen; do not continue speaking when they are not directing their attention toward you.

When a child gets frustrated and begins to act inappropriately, teach them and help them to regulate their emotions. Sometimes a “time out” where they may sit for a moment and think about the poor behavior they just exhibited helps them gain control of their emotions, whereas a parent’s continued interaction with the inappropriate behavior (repeatedly asking them to stop while getting angrier) can escalate emotions and not teach self-control. Of course, a parent or teacher must model emotional self-control and when they fail, as we often do, say “I let my emotions get out of control. I need to work on that”.

Show children how to plan. Look for opportunities when a child failed to plan well, such as forgetting to bring something, and talk about strategies for remembering or planning, such as laying materials out the night before. Talk to children about the choices they made and discuss how they could use better judgment. Let children struggle a little to solve their own problems before you jump in, but guide them with suggestions such as “instead of getting upset, let’s think about how you can solve this problem.”

The most important skill you can teach your child is metacognition – thinking about their thinking. Ask questions that require the child to reflect on behavior or consequences, such as “how do you think your friend felt when you did that?” or the statement that is usually sarcastic but shouldn’t be in this case –“what were you thinking?” Require children to stop and pause and look inside.

We would say in our research laboratory, “good frontal lobes, good life”. Scientists know the importance of these higher-order thinking skills involved in frontal lobe executive function. Start early teaching these skills and continue until they reach adulthood. Help them create the brain that will serve them well in life as well as school.